|

|

Nickel allergy |

|

De Janice Joneja discusses its diagnosis and management |

|

Nickel related food allergy was first suspected when dermatologists noticed that some people had outbreaks of dermatitis on skin that had not been in contact with any known allergens. They suspected that the allergen might be something that these people had eaten and so looked for sources of known contact allergens, such as nickel, in commonly eaten foods.(3) Nickel occurs naturally in many foods and can also be introduced into the food during processing – from metal cooking utensils or containers, for example (4). Dermatitis, especially on the hands, may develop as a secondary response to nickel sensitisation and the rash may later spread to other body surfaces. This may be a reaction to nickel in foods in those who were initially sensitised by direct skin contact with nickel. (5) Cases of erythema multiforme (6) and vasculitis (7) have also been occasionally reported after eating nickel-containing food. Diagnosis of Nickel Allergy As with any contact allergy, diagnosis is by a patch test. The nickel allergen (usually in the form of nickel sulphate) within the patch is placed on the skin and left in place for up to 72 hours. The area under the patch is usually observed after 48 hours. Because type IV hypersensitivity is a delayed response, the reaction may take 2 to 3 days to become visible. In a positive reaction, the area of skin under the patch will turn red and possibly itch and blister if the reaction is severe. Dermatitis triggered by nickel in food is usually suspected when a chronic dermatitis persists without obvious contact with nickel-containing objects. Elimination and challenge is at present the only method to identify this cause of the reaction. A low-nickel diet is followed for a period of 4 weeks. If the rash subsides, a challenge with foods with high nickel content will usually indicate that ingested nickel is a trigger for the reaction. (8-11) The level of nickel in foods Because all foods contain some level of nickel, a nickel-free diet is not possible. However, some foods are much higher in their nickel content than others. Levels can vary according to the variety of the plant species or the nickel content of the soil in which the plant was grown or, in the case of seafood, of the aquatic environment. In addition, different laboratories employ a variety of tests to detect nickel in food, so frequently data from one source can disagree markedly with that from another. In most studies, the richest sources of dietary nickel are found in nuts, dried peas and beans, whole grains, and chocolate. In addition, processing a food can increase its nickel content. For example, minute traces of nickel from metal grinders used in milling flour can increase the nickel in flour considerably, and stainless-steel cookware will increase the level of nickel in the food cooked in it. As a result it is difficult to get an accurate picture of nickel levels in most foods.. A comprehensive table of nickel levels in foods can be found in Reference (11) below. In addition, there a number of internet sites that provide information, for example, the lists for Penn State Hershey Medical Center or the Melisa Foundation. Nickel and Iron However an increasing number of studies are now suggesting that oral exposure to nickel may help to reduce the severity of dermatitis caused by direct contact with related to nickel or even prevent it. (12,13) According to other studies, oral exposure to nickel can worsen established nickel contact dermatitis initially, but prolonged exposure can reduce the clinical symptoms. (14) But the subject of nickel-contact dermatitis, nickel allergy, and achievement of tolerance is confusing from a practical point of view because of the extremely complex series of events that occur in the immune system. Nickel contact dermatitis is part of a cell-mediated (type IV) hypersensitivity reaction; nickel allergy is possibly an IgE-mediated (type I) hypersensitivity (15) and the precise mechanism that allows the immune system to achieve tolerance, especially to foods, is unclear at present. Management of allergy to ingested nickel Clinical studies suggest that some nickel-sensitive people benefit from avoiding foods with high amounts of nickel. However, opinions differ on what constitutes a nickel-restricted diet. In one research study, an oral dose of nickel (as nickel sulfate) as low as 0.6 mg produced a positive reaction in some nickel-sensitive people. (16) Another report indicated that 2.5 mg was required to induce a flare-up. (17) Because the levels of nickel required to induce a reaction have varied widely in different studies, it is difficult to determine a ‘safe level’ of dietary nickel for nickel-sensitive people. However, dietary nickel often is not the sole cause of the dermatitis. In these cases, avoiding nickel in the diet may improve the situation but does not entirely eradicate the symptoms. If symptoms have resolved on the diet, challenge with foods with high nickel content should lead to a flare-up of skin reactions if a person is indeed allergic to dietary nickel.

Additional Resources You can buy all of Dr Joneja's books here in the UK or here in the US. First published February 2014 |

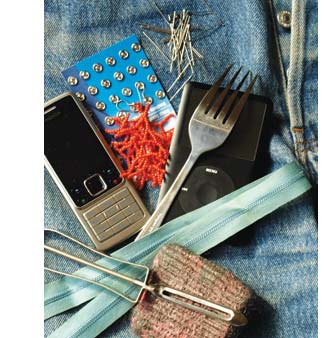

In nickel-sensitive people, a rash called contact dermatitis develops where the nickel has been in contact with the skin or mucous membrane for a period of time.(1) The reaction often occurs when the nickel-sensitive person is in direct contact with nickel-containing items such as jewelry, metal studs, watchbands, belt buckles, thimbles, and other metal-containing objects. The reaction is known as a cell-mediated delayed hypersensitivity (type IV hypersensitivity) reaction. Contact with the nickel induces local T-cell lymphocytes to produce cytotoxic cytokines that cause the itching, reddening, and scaling typical of dermatitis.(2)

In nickel-sensitive people, a rash called contact dermatitis develops where the nickel has been in contact with the skin or mucous membrane for a period of time.(1) The reaction often occurs when the nickel-sensitive person is in direct contact with nickel-containing items such as jewelry, metal studs, watchbands, belt buckles, thimbles, and other metal-containing objects. The reaction is known as a cell-mediated delayed hypersensitivity (type IV hypersensitivity) reaction. Contact with the nickel induces local T-cell lymphocytes to produce cytotoxic cytokines that cause the itching, reddening, and scaling typical of dermatitis.(2)