|

|

|

Why ‘Vegan’ may not always mean ‘Milk Free’ |

Alex Gazzola explores why relying on a ‘vegan’ or ‘vegetarian’ label is inadvisable when you have a food sensitivity to an animal-sourced ingredient. |

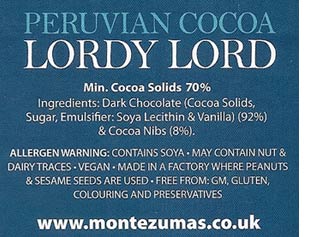

If, like many with allergies and intolerances to animal ingredients, you would – you’d be forgiven for thinking so. Yet this may not be the case. “The Vegan Society does not claim trademarked products are suitable for people with allergies such as dairy allergy,” says the Society’s Jimmy Pierce. “That will depend on the standards achieved by individual manufacturers.” He adds: “While The Vegan Society requires manufacturers to do all they can to minimise cross-contamination, we accept some trademarked products may carry warning labels such as ‘may contain milk’ because this refers to accidental low-level cross-contamination. Even after thorough cleaning some cross-contamination may occur on production lines that are not dedicated to vegan products. Low levels of dairy contamination are likely if a vegan chocolate is manufactured after a milk chocolate, for example.” Very few chocolate manufacturers have dedicated milk-free lines on which to produce their dark chocolate lines, for example, and therefore not surprisingly many of their products carry dairy allergen warnings. This one pictured making a vegan claim is of a bar of Montezuma chocolate, and the allergy and free from blogger Sugarpuffish has posted another example, which is Vegan Society registered, by Organica. But other foods – such as these quinoa crisps by Cofresh – may also claim to be vegan yet carry a dairy-related disclaimer.

Indeed, The Vegan Society’s very definition of veganism mentions excluding animal products ‘as far as is possible and practicable’. But is that enough for those with food allergies? Controversy and disagreement “The Society’s acceptance that the term ‘vegan’ can be used with ‘may contain milk / eggs / fish’ seems to be fixated on the premise that the term is only used to indicate possible low levels,” says Adrian Ling of vegan and ‘free from’ manufacturers Plamil Foods. “This fails to recognise that it also applies to significant contamination, and in reality allows a manufacturer to not be as vigilant as possible to prevent contamination.” The Society’s stance would also appear to be at odds with 2006 guidelines from the FSA (clause 17), which state that “manufacturers, retailers and caterers should be able to demonstrate that foods presented as ‘vegetarian’ or ‘vegan’ have not been contaminated with non-vegetarian or non-vegan foods during storage, preparation, cooking or display”. Olu Adetokunbo of the FSA’s Food Safety Policy Division told us it was the FSA’s view that it was “misleading to have ‘vegan’ and ‘may contain dairy traces’ on a food product”. He added: “Article 16 of EC Regulation 178/2002 prohibits labelling or other presentation which misleads consumers. This is enforced by means of the General Food Regulations 2004 in Great Britain. The Regulations also specify offences in relation to the requirements and impose penalties for these offences. These penalties are consistent with those currently in operation under the Food Safety Act 1990 for food law offences – the enforcement of which is primarily (but not solely) the responsibility of more than 400 local authorities in the UK, and more specifically Environmental Health Officers (EHOs) and Trading Standards Officers (TSOs).” Although Ling believes the term ‘vegan’ may reasonably mean slightly different things to different people, he argues the labelling regulation is clearcut when it concerns the term’s use alongside a ‘may contain milk’-type warning. “There are many labels on the market which do not follow regulations and TSOs have little time to notice and enforce, leaving consumers to think these labels are OK,” he says. “There would be more cases of withdrawal or label clarity if ‘policing’ was more comprehensive.” Vegan and vegetarian labelling are the responsibility of the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). Despite our placing a number of calls and sending several emails to DEFRA’s press office, the Department would not explicitly confirm whether or not they agreed with the FSA that a ‘vegan’ claim alongside a ‘may contain dairy’ (or egg) claim was misleading, and therefore illegal, and declined to explain why they would not do so. We were given only the following statement: A Defra spokesperson said: “Food producers must adhere to strict rules governing allergen labelling – ‘vegetarian’ and ‘vegan’ are terms used voluntarily by industry, though there are still laws requiring this information to be accurate. Local authorities are responsible for enforcement of trading standards.” But how can the terms ‘vegetarian’ and ‘vegan’ be used in an “accurate” way, when no legal definition for the terms exist? Allergen Considerations NGCI itself is not necessarily equivalent to gluten-free, which means under 20 parts per million of gluten – ie less than a specified quantity – although NGCI is to be used only when cross-contamination measures are in place. Analogously, the Vegan Society’s definition of ‘vegan’ does not require a food or drink to fall below a maxmium dairy or egg (or indeed fish) threshold, but it does request that the manufacturer ‘diligently’ looks to manage potential cross-contamination. Although ‘free from’ thresholds for all allergens other than gluten have been promised for some years, neither ‘milk free’ / ‘dairy free’ nor ‘egg free’ are yet defined in ‘parts per million’ terms. And in the absence of such an assigned permitted maximum for milk traces in so-called ‘dairy free’ foods, the default definition must legally be taken to be ‘no detectable levels’ of milk. So how low can the laboratory analyses go in detecting milk allergens? And which of the many milk proteins should be tested for? “We would normally test for casein proteins, which form 80% of the total milk proteins, and tests can go as low as 0.2ppm,” says Dario Deli of Romer Labs. “We would also test beta-lactoglobulin [a whey protein] and this test is even more sensitive – ten parts per billion (0.01ppm). Although we don’t test for lactose at Romer Labs, the lowest limit of detection for it is around 10ppm.” Most companies, says Deli, tend to accept a negative test result as a ‘pass’, and a non-negative test as a ‘fail’ – in the absence of a defined ‘free from’ limit, manufacturers must aim for as low as they can go. “If you make a milk or dairy free claim, you are implying it is casein-free and beta-lactoglobulin-free, according to the lowest limit of detection,” he says. “A negative test for casein implies you can assume there is no known casein present – but it wouldn’t be able to detect 0.1ppm, for example, as the limit is 0.2ppm.” One can assume that most manufacturers making ‘dairy free’ claims submit their products for such testing, but how many making only ‘vegan’ claims do so? And if they don’t, should they be using a modified term or claim – such as ‘vegan ingredients’, perhaps – instead of ‘vegan’? It’s worth bearing in mind that contamination issues can befall even the most highly regarded and established vegan operations – VBites, for instance, last summer had to recall batches of its ‘Wot, No Dairy?’ vegan dessert due to presence of detectable levels of caseins. Ling points out that there is a further issue for vegans who wish to avoid products carrying ‘may contain’ warnings against non-vegan allergens – they almost certainly wish to avoid non-vegan non-allergens too. The problem is there’s no obligation on food producers to declare possible trace cross-contamination with meat, honey or other animal-sourced ingredients which are not among the ‘14 allergens’, and none to recall any products which are found to contain them. Guidance Rewrites Furthermore, DEFRA is also seeking views on whether foods carrying precautionary allergen statements should be allowed to be presented as ‘vegetarian’ or ‘vegan’ where the allergen referred to is not considered to be suitable for vegetarian or vegan diets. These can be sent to them at labelling@defra.gsi.gov.uk. Until the issue is resolved, bear in mind that a vegan claim or symbol may help guide you towards a possibly safe choice if you have certain food allergies – but it certainly doesn’t come close to being a confirmation of one. As always, it pays to remember the cardinal rule – read labels every time. April 2015

|

Would you infer from a label reading ‘vegan’ that the food within was dairy / milk free – and indeed egg free and fish free? What about if the product was additionally registered with the Vegan Society, and bore its trademark logo?

Would you infer from a label reading ‘vegan’ that the food within was dairy / milk free – and indeed egg free and fish free? What about if the product was additionally registered with the Vegan Society, and bore its trademark logo?  A statement has been added to the Vegan Society Trademark licence agreement to encourage manufacturers to commit to avoiding cross-contamination. It reads: ‘I confirm our company strives diligently to minimise cross-contamination from animal substances used in other (non-vegan) products as far as is reasonably practicable.’

A statement has been added to the Vegan Society Trademark licence agreement to encourage manufacturers to commit to avoiding cross-contamination. It reads: ‘I confirm our company strives diligently to minimise cross-contamination from animal substances used in other (non-vegan) products as far as is reasonably practicable.’